Super Bowls SDSU Connection: A 24-Minute Miracle

Secrets of the halftime show, including the two words field team manager Bryan Ransom never uses with the crew responsible for assembling a stage.

“It’s so much work, but I can’t wait to get back out there.”

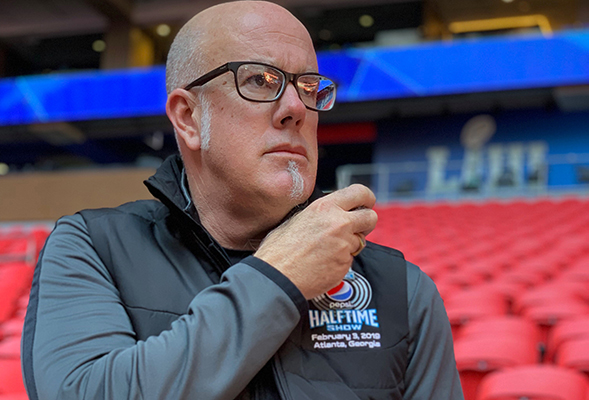

It was Feb. 4, 2007, and San Diego State University’s Bryan Ransom was working his sixth Super Bowl as field team manager, the person in charge of getting a huge stage into place for the highly anticipated halftime show.

The performer was Prince. The city was Miami. The location was Dolphin Stadium and it had no roof.

“We knew a couple of days before that there was a big storm coming,” recalled Ransom, who’s currently back in Miami for the NFL’s Super Bowl LIV and a Pepsi Halftime Show co-starring Jennifer Lopez and Shakira. “We were all glued to satellite images watching this giant ‘blob’ of a storm coming right for us.”

The field team, anywhere from 500 to 800 people, moves as many as 50 separate pieces into place to build the stage. Everything has to fit together just right, and the assembly has to be completed in under seven minutes.

The rain at game time was getting worse as the second quarter was ending, bad enough to raise concern the live performance would have to be scaled back or even scrubbed. “But we’re there to put on a show,” said Ransom, director of marching bands for SDSU. “Really nothing to do at that point but execute what we had been working on for months.”

The result, brought off amid a downpour, is widely regarded as one of the greatest Super Bowl halftime shows ever. Prince—who was later quoted as having asked a producer “Can you make it rain harder?”—had a setlist that included “Let’s Go Crazy,” Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” and, of course, “Purple Rain.”

Ransom is one of two SDSU faculty with a role at the game. Jay Sheehan, production manager for the School of Theatre, Television, and Film, will again be technical director of GameDay Fan Plaza, a pre-game event at the stadium.

Sunday will be Ransom’s 19th Super Bowl, and while football fans have a good idea what it took for the San Francisco 49ers and Kansas City Chiefs to get there, the preparation required to pull off the halftime show isn’t nearly as well appreciated. Working under a professional and experienced production company hired by the NFL, Ransom usually arrives on site three weeks before game day to begin the planning.

“We call it the 24-minute miracle,” Ransom said in a late December interview in his second-floor Music building office, where one wall is lined with photographs from each of his shows. “We have…as much as seven minutes to get the stages onto the field, usually a 13-minute show, and then four minutes to get it off before the teams come back out.”

Ransom originally got involved in the halftime show through a contact with the Michigan State University marching band who wanted help with a Super Bowl pregame show—and knew that marching band veterans understand the terminology and the configuration of a football field. His involvement since then has grown to include the post-game ceremony as well. On Jan. 13 in New Orleans, he also completed his sixth year as field producer for the College Football Playoff National Championship pregame show.

The halftime field team is composed primarily of men and women recruited locally, Ransom said, but there’s now a “travel party” of about 150 people who join him to work the event every year. Ages range from 18 to 80. “They’re not stage people,” he said, “they’re just people, and we teach them how to properly steer each one of these pieces.”

These modular, rolling pieces (including speakers) typically number 40 to 50, each with its own stage manager, with some raised into position on hydraulics.

The field staging rehearsals begin about two weeks before the game with at least four run-throughs done without the featured artist or band. If the fans surrounding the stage, jumping and waving their arms during the actual performance, look like they know what they’re doing it’s because they do—they’re all cast members, trained in the rehearsals on where to stand and what to do to recordings of the planned music.

Game day is quite a bit more complicated, since the stage units usually need to be moved in through the same tunnel the teams are using to get to their locker rooms. And even though speed is a critical issue, Ransom said the two words he never, ever, uses with his crew are “hurry up.”

“Safety is the number one priority and we preach it from day one,” he said. “Because it’s inherently dangerous to have people pushing these things faster than they can make them move.”

“It’s so much work,” he said, “but I can’t wait to get back out there.”

Sheehan also arrived in Miami weeks ahead of the game to help plan security at the entries, a tailgate party and the Fan Plaza, a family-friendly entertainment zone with music, games and other entertainment. This will be his fourth time as production manager.

“It’s a three-week build, a four-hour party and a one-week teardown,” Sheehan said. “It’s quite a production.”