SDSU APIDA Center Director Aims to Transform K-12 Education with Comprehensive Asian American History Curriculum

Virginia Loh-Hagan's Asian American Education Project shines light on Asian American history and aims to impact K-12 students across U.S.

On campus, Virginia Loh-Hagan is known as an educator and an advocate who impacts scores of students as director of SDSU’s Asian Pacific Islander and Desi-American (APIDA) Center.

Beyond the walls of San Diego State, Loh-Hagan’s combined passions for education and Asian American advocacy could impact millions of America’s youngest learners.

She is the co-executive director and curriculum director of The Asian American Education Project (AAEdu), which creates and provides curriculum and professional development for K-12 schools — offering a more comprehensive and accurate look at APIDA history.

“The reason why it’s important is because we haven’t heard these stories or these histories; we (as Americans) have been focused on a white, patriarchal, middle-class narrative for a long time. Many other folks have contributed to American society, and not just white people,” Loh-Hagan said. “A lot of people have contributed to the American narrative.”

This hits home for Loh-Hagan, whose family is ethnically Chinese but fled to Cambodia during the Japanese occupation and then were granted U.S. asylum during the Cambodian genocide of the 1970s. She said she didn’t learn much about her heritage or Asian American contributions to American society until her college years.

“It wasn’t until I took an Asian American studies class at the University of Virginia, and I was like ‘Whoa, we have a history?’” Loh-Hagan said. “When my parents first arrived in the United States, it was about assimilation, a desire to fit into society, which meant denying your own cultural background. So growing up, I didn’t know much about my culture. I just knew I was different.”

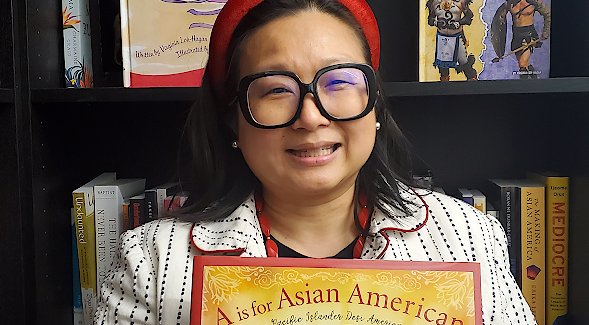

Loh-Hagan has been in the APIDA advocacy space for years as a teacher (she had taught in K-8 schools in La Mesa-Spring Valley and Chula Vista school districts), as a teacher educator at SDSU and as an author — she has over 400 titles to her name. Her latest book, released in 2022 by Sleeping Bear Press, is entitled “A is for Asian American.”

She did an author talk on one of her books, “Paper Son,” at Casa de Oro Elementary in Spring Valley, which caught the attention of the school librarian, who connected Loh-Hagan to her brother and sister-in-law, who were working on an important docuseries.

The librarian’s brother was Stewart Kwoh, a longtime civil rights activist and attorney, who was working with his wife, Patricia, to develop a curriculum for the five-part series for PBS called “Asian Americans.”

Kwoh brought Loh-Hagan aboard to help lead the team in developing elementary lesson plans tied to the docuseries.

Two years later, the Kwohs founded The Asian American Education Project, following the rise of anti-Asian bias and hate speech during the COVID-19 pandemic, in an effort “to bring the history, contributions, challenges and triumphs of Asian Americans to students across the country,” according to its website.

Stewart Kwoh, the first Asian American attorney to earn a MacArthur “genius grant,” said Asian American history is largely absent from the current K-12 curriculum, but the project aims to change that paradigm.

“As we have moved around the country, done training in 10 states and trained over 4,000 teachers, we have found that APIDA history is pretty invisible throughout the country,” Kwoh said. “Making Asian American history visible is a huge undertaking and very necessary. There is a lot of enthusiasm among teachers, but they really don’t know anything about our history, so it is incumbent upon us and others to bring that history to them.”

Loh-Hagan joined the project as a co-executive director and curriculum developer. AAEdu has the goal of reaching 1 million youth with its lesson plans and trainings within five to seven years.

The lesson plans span the arrival of the first Asians to the North American continent in the 1700s to the present day. Some of the topics include the arrival of the “Manilamen” (the first Filipino immigrants to settle in Louisiana around 1763), the contributions of Chinese transcontinental railroad workers during the 1860s, Japanese American incarceration, South Asian pioneers in California, the Native Hawaiian sovereignty movement, the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees as well as Asian American military service during World War II and Asian American breakthroughs in Hollywood and cinema.

“She’s been a tremendous contributor; she’s outstanding in curriculum development in particular, and she’s added over 20 new lesson plans to our curriculum,” Kwoh said. “Virginia is crucial to our goal of reaching 1 million students.”

Loh-Hagan said that the rise in racism and violence against Asians during the pandemic underscored the need for the project and its curriculum.

“I know as an educator I’m biased, but I firmly believe that education is the most effective long-term solution for combating anti-Asian hate and changing generations,” she said.

Meanwhile, Loh-Hagan, who worked in the College of Education, serving as director of Liberal Studies, leading the three-semester teacher credential programs, and teaching teacher education courses for more than 10 years before becoming APIDA Center director in 2020, said that she feels the center has made a huge difference on campus. It raises awareness about issues that Asian Americans face, celebrates APIDA culture and amplifies the contributions of APIDA Americans to a campuswide audience, she said.

“This is where I get excited, because the fact that we have more people on campus who know what APIDA means, I feel like we have made our presence felt,” Loh-Hagan said about the community center that is entering its third year on campus. “There are folks who tell us that they’ve enjoyed our events, they’ve read our newsletter and learned something new when they read it. So I do think we’re making a difference and we have a space that is available to serve our APIDA-identifying students, faculty and staff and allies.

“We want to be seen as the hub and be renowned for our work in growing the voice and visibility of APIDA communities on campus,” she said. “I have big dreams and a loud voice and intend on using them.”

Loh-Hagan said AAEdu has also been an invaluable partner of the center, providing curriculum and even financial support.

“It’s been a good partnership; our goals are similar, and it fits what we are doing here at SDSU,” she said.

Between AAEdu, her books, and the center, Loh-Hagan said she feels she is in a position to continue to affect change. All of these endeavors work collectively to increase awareness and education about the APIDA experience.

“When I was a K-8 classroom teacher, I could have a great impact on the 20-30 children in my classroom, but my platform is different now. I can reach a lot of people, and I hope to be able to do that,” Loh-Hagan said. “Curriculum writing isn’t sexy; it doesn’t get news. But what it does do is change generations. It is a slow, laborious process, but ultimately, if you stay committed, the impact can be generational.”

To learn more about its curriculum and lesson plans, visit The Asian American Education Project. Visit the APIDA Center website.