SDSU Engineers Enhance a Sustainable, Cheap Toilet Alternative

An innovative low-water toilet offers dignity and sanitation for underserved communities.

Environmental engineers at San Diego State University optimized a low-cost, low-water toilet that they are hoping to provide to homeless, rural and refugee populations who often lack regular, safe access to restrooms.

“America is the epitome of the flush and forget system,” said Lilith Astete Vasquez, an environmental engineering doctoral student at SDSU and lead author of a recent Scientific Reports paper demonstrating the scientific benefits of low-water toilets she designed.

It is common practice in most American restrooms to use drinking water to flush away feces, along with toilet paper and urine. Waste treatment happens out of sight and out of mind.

But in communities where water is scarce due to drought or contamination, human fecal waste stays in place above ground or in a dugout hole. This increases risk for the spread of disease and contamination of nearby water sources.

To solve the need for sanitary toilets that use minimal water, Astete Vasquez took inspiration from a solution her advisor, engineering professor Natalie Mladenov, encountered in rural Botswana.

In the late 1990s, in the middle of a field working on her master’s degree on polluted rivers, Mladenov found herself needing to go. She was pleasantly surprised to learn that she would not have to defecate out in the open, still a common practice among 7% (over 550 million people) of the world’s population, according to the World Health Organization.

Instead, the option available to her was a toilet far superior than a chemical-based Porta Potty or a putrid hole in the ground; it flushed without any pipes and without any undesirable smells. The contents were still stored nearby in an underground reservoir, but each flush mixed them with previous deposits, no additional water necessary.

Mladenov and Astete Vasquez designed an experiment to understand how waste decomposes in this rural toilet, with a little help from Astete Vasquez’s three dogs: a rat terrier named Canyon, and chihuahuas Taco and Peach.

Lending a Paw

For nearly two years, Astete Vasquez would pick up her dogs’ feces and store it in her fridge (in a biosafe container) before bringing the samples to campus.

“Dogs have the closest gut microbiota to humans,” Astete Vasquez said, adding that they often eat a more balanced and nutrient-rich diet than she does.

These attributes made the dogs’ waste a superior (and free) stand-in for cow manure, the typical option in research on septic systems.

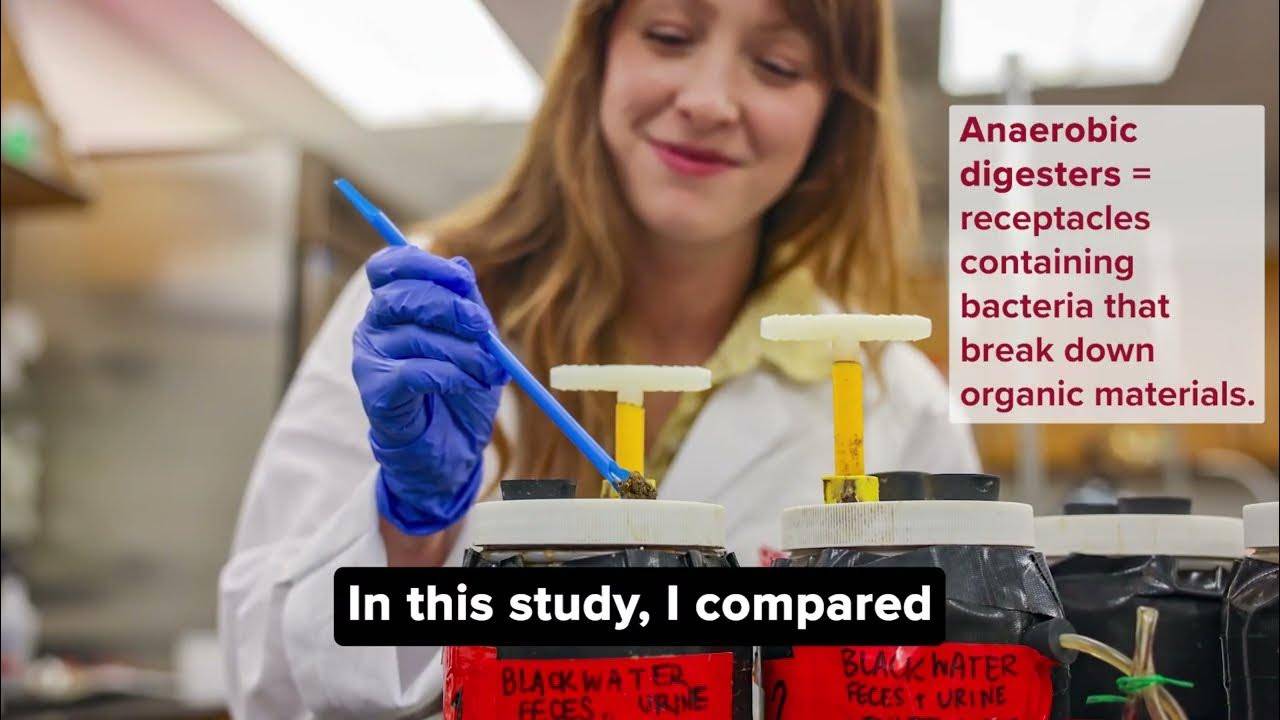

Twice a week, she would add the canines’ fecal matter into simulated toilets made from some jars and deconstructed dollar-store Super Soakers plungers, then mix up the contents. This lab-based, tabletop approximation of the Botswana toilet enabled careful and long-term monitoring of the color, density, smells and chemical composition of the waste over time.

“This was a fundamental lab experiment looking at what happens inside of the receptacle for the waste,” Mladenov said. “These experimental conditions simulate what happens, for example, in a septic tank or a cesspool that’s not mixed versus another system that is mixed.”

Stirring up the waste a few times with a plunger resulted in the best decomposition and least smell, with the liquids and solids combining into a homogeneous milkshake-like texture. These advantages persisted over several months compared to letting it stagnate while still using minimal water.

Real World

In addition to testing the benefits of mixing up waste, the environmental engineering duo wanted to know how the experimental toilets would handle different defecation customs, like excluding toilet paper or separating urine from feces.

Thanks to bacteria that don’t need oxygen to survive, the lab-based receptacles functioned well and clogged infrequently. Using a scaled up version of these toilets holds promise for reducing maintenance of existing pit toilets.

“Lily’s work is fantastic in that it’s simulating real-world scenarios that are important for developing and developed world situations,” Mladenov said.

Their mixing toilets’ minimal water use and adaptability to cultural practices could be implemented in refugee and rural situations around the world. In places where setting up plumbing for off-site wastewater treatment is not possible, using a simple plunger and a little bit of recycled water to move and strain contents through a tube to a container adjacent to an outhouse could function well enough for more than six months.

Based on the results of her study, Astete Vasquez is currently in the process of patenting a low-water, mixing device that can be retrofitted into existing rural septic systems. Once patented, she plans to install some in national parks and in mobile hygiene trailers operated by ThinkDignity, a local non-profit organization that serves San Diego’s homeless population.

“Everyone poops. And no one wants to think about where we’re putting the poop or what we’re doing with the poop.” Astete Vasquez said. “Just having a safe place to do it, that should be an inherent right, a human right.”