Celebrating 60 years of doctoral level chemistry

The stories of three San Diego State alumni ― a nun who investigated cancer treatment, a leader in medical diagnostics, and an expert in semiconductor science ― who made an impact.

Sixty years ago, the Joint Doctoral Program (JDP) in Chemistry became the first doctoral degree program at what was then San Diego State College, and the first in California’s statewide college system.

Created in partnership with the University of California San Diego, the program was a key step in expanding graduate degree offerings across the 22 institutions comprising today’s California State University system.

What began as a single doctoral program in chemistry became the catalyst for a culture of scientific discovery, fueling new programs, and ultimately helping the university achieve its prestigious R1 research status.

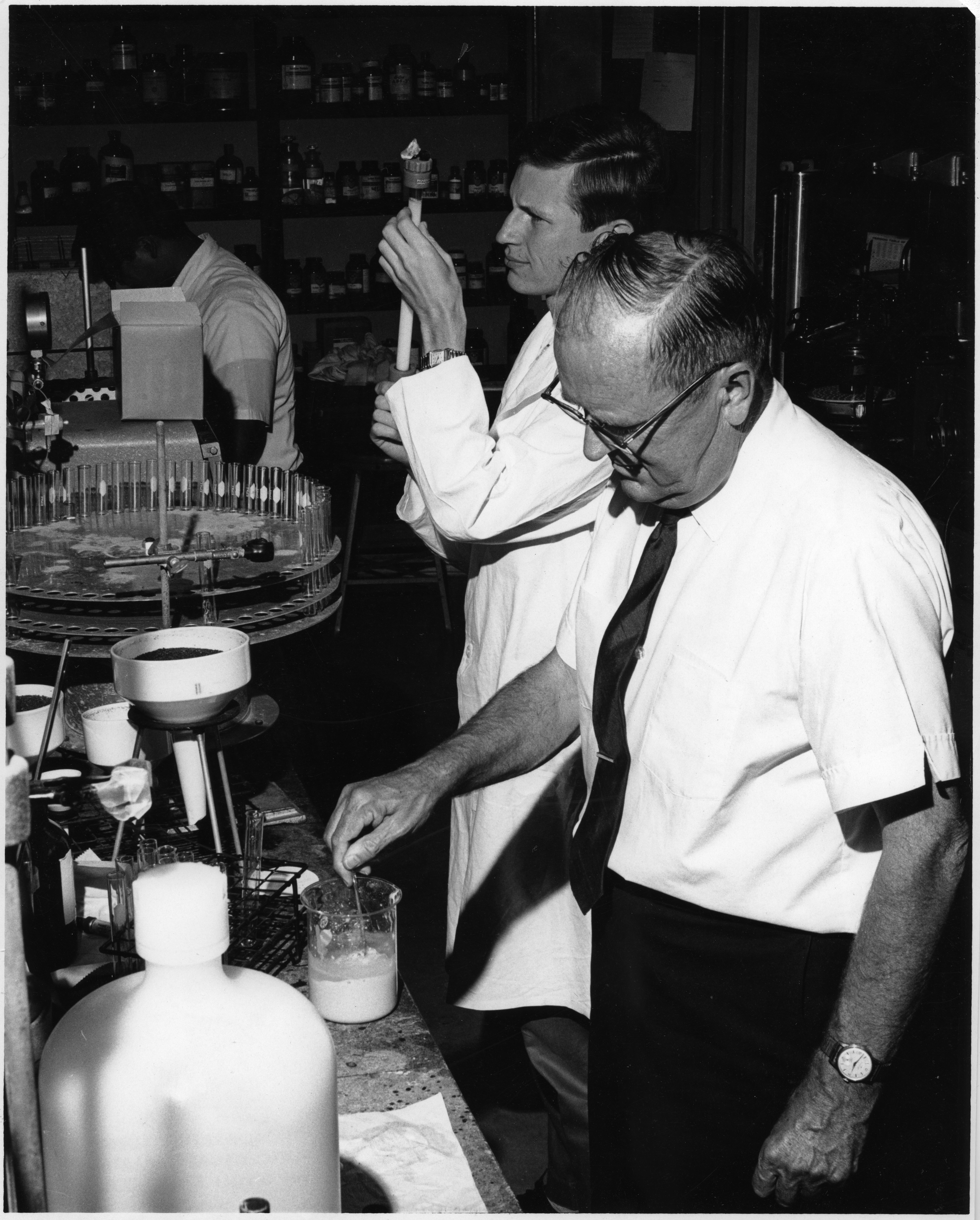

In 1950, the college’s undergraduate chemistry curriculum was the first within the state system accredited by the American Chemical Society. With a new building constructed in 1960, the department had the facilities needed to continue conducting high-level science and training students.

By the 1960s, the chemistry faculty had been conducting funded research for 20 years. During this time, the department continued to recruit professors with research experience and active grants.

This momentum culminated in the next critical step for advancing the department and university’s impact: building a doctoral program.

In fall 1965, after negotiations with newly founded UC San Diego, the Joint Doctoral Program in Chemistry was officially established. In June 1967, Robert Metzger became the first student to graduate from the program, earning San Diego State’s first Ph.D. degree. He went on to serve as a professor of biochemistry and is now a professor emeritus at SDSU.

A New Era of STEM

Creating the chemistry JDP was a critical move for advancing STEM research and teaching.

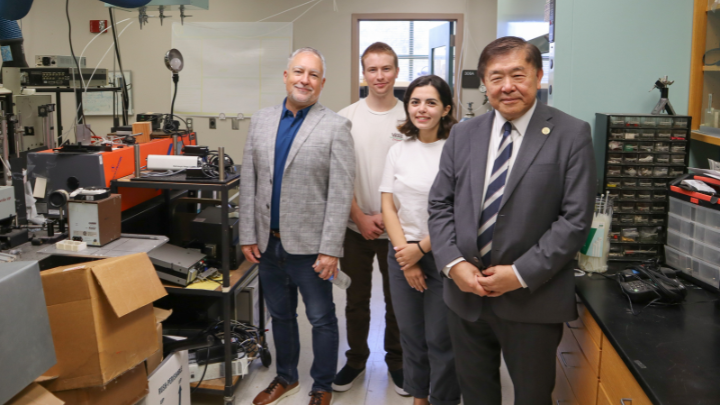

Provost William Tong first began teaching chemistry at SDSU in 1985 and overlapped with several of the JDP founders. Recalling those early years, he credits Professor Harold “Hal” Walba, who served as chemistry chair at the time, and President Malcolm Love, as especially instrumental in the program’s implementation and long-term success.

“Without the JDP program, we wouldn't be an R1 today,” Tong said. “To be considered R1, you have to have a minimum amount of research grant activities and a certain number of doctoral graduates every year. Now, we have about 30 doctoral programs and our research funding is around $250 million per year.”

Today, collaboration with UC and other JDP partner universities remains strong. Still, decades later, SDSU offers the only chemistry doctoral program in the CSU system.

After 10 years, SDSU Georgia has graduated many chemistry students, some of whom have continued their chemistry education through the JDP in San Diego.

“The Joint Doctoral Program in Chemistry exemplifies SDSU's commitment to advancing STEM initiatives that train our students for their future careers, while benefiting local communities and beyond,” said Jeffrey T. Roberts, College of Sciences dean.

Here are three stories from the program’s history:

1) Sister Scientist

Sister Patricia Shaffer (’75) was the first woman to graduate from the chemistry JDP. A nun, professor and researcher at the University of San Diego, she earned the nickname “sister-scientist” and played a key role in bolstering USD’s biochemistry research activity.

“The thing that sticks with me most is how much of a builder she was,” said Mitchell Malachowski, USD professor of chemistry and biochemistry. “When she came, she was the only biochemist in the department. Now we have a thriving biochemistry program that she helped start. She was the first biochemistry person to do research so she was creating a whole new world for everybody who came after her.”

Sister Shaffer belonged to the Society of the Sacred Heart, which encourages sisters’ doctoral education to support their teaching vocation. She entered the religious order during her undergrad years and went on to teach up to eight classes a year, mentor undergraduates in her chemistry lab and regularly publish research papers, constantly seeking new solutions and grants to fuel them.

“One word that strikes me to describe Sister Pat is commitment,” said Tammy Dwyer, USD professor of chemistry and biochemistry. “My first year, a student in my class earned a D. The next year, I remember walking past Pat's wing and I saw that student in the lab. He started doing research with Pat and it caught fire. She saw something in him, inspired him and when he graduated, he ended up being one of our top majors.”

Even after she graduated from the chemistry JDP, SDSU supported Sister Shaffer’s work exploring metabolic pathways and enzymes in fungi that could offer insight on treating certain cancers.

“Faculty there were very supportive of her throughout her career. When she retired, she wanted to stay active in research but we didn't have any space for her,” said Dwyer. “She would actually use space over at San Diego State to keep her research program going and USD students would go and work with her.”

Sister Shaffer performed her academic, philanthropic and religious duties, while being there for “any student who needed a listening ear,” until her passing at age 96 in Dec. 2024.

“She was a force of nature about everything. People still talk about her, students remember her, so it extends well beyond her life on Earth,” said Sister Mary Hotz, USD associate professor of English. “At USD, she was very active in teaching and scholarship, the Founders Club for student outreach, ministry programs and the women's basketball team. If you went to a game with her, she could look across and name all of the people there, what she taught them and what year they graduated.”

2) Mentorship Spanning Decades

The same dedication that guided Sister Shaffer’s work continues to shape generations of researchers who follow. Among them is Jon Nunes (‘89, ’94), whose path was similarly influenced by the mentorship he found in SDSU’s labs, especially one in particular.

Growing up surrounded by farms and dairies in rural central California, Nunes was more interested in science and technology than agriculture, and turned to SDSU to pursue a career in STEM.

“My dad died when I was young so my mom raised me and my two younger sisters, and she was always adamant that I was going to college under any circumstances,” Nunes said. “The question was what could we afford and the idea of getting as far away as I could to experience something new. San Diego was the perfect fit.”

During his second undergraduate year, Nunes was introduced to Professor Tong’s lab by a teaching assistant in one of his classes. There, Nunes began conducting cutting-edge spectroscopy and photonics research, using lasers to analyze the chemical composition of different substances. The experience helped him discover his passion for research, and he decided to continue his studies at SDSU and pursue his Ph.D.

“I really loved what the group was doing and it gave me a focused approach to finishing my degree,” Nunes said. “I worked as a teaching assistant all the way through graduate school so the support I got from that, together with the funding options through the Joint Doctoral Program and the idea that I could transition my undergraduate research into my graduate research, why wouldn't I do it?”

As a vice president of development at Roche Molecular Systems, Nunes said his hands-on training and unique research at SDSU prepared him for the medical diagnostics field.

“To this day, when we develop new diagnostic equipment, it almost always comes down to either some type of optical or electrochemical detection,” he said. “My core understanding of those technologies came directly from what I was working on in the lab as a grad student.”

“It's great to see the California-based university systems developing more and more students to have skills that, frankly, industry needs,” he added. “My fondest memory of the JDP is the genuine support I received from my mentors — a contribution I will never take for granted.”

3) Lasting Impact

Like Nunes, Barbara Sawrey (‘83) discovered her calling as a SDSU chemistry graduate student.

“Part of the strength at SDSU was helping people who were unsure to figure out, was a master's degree the end goal or was it the beginning of getting into a Ph.D.,” she said. “People came from many backgrounds and SDSU was always so accepting of students at all levels.”

The daughter of an engineer, Sawrey was immersed in STEM from a young age. After earning her undergraduate degree, she studied the science behind flavors and fragrances as an industrial chemist.

“When I was working, I realized, while I had a reasonable amount of chemistry knowledge and experience, and I was gaining more all the time, I needed to go to graduate school,” she said. “There was so much more I needed to learn.”

Entering the chemistry master’s program at SDSU, Sawrey was nervous about returning to school after five years.

“The faculty in the chemistry department took us under their wings and helped us through,” she said. “It turns out my years out of school were not a detriment. My work and study habits were improved by that time in industry. At the end of the first semester, when I aced my classes and fell in love with being a teaching assistant, I thought, wow, I'm home.”

Sawrey worked with chemistry professors Ed O'Neal and Morey Ring on efficient ways of making pure silicon, which involved carefully extracting it from the compound silane, which could burn or explode on contact with air. The group studied the thermodynamics and kinetics of controlled explosions created in this process, for application in emerging semiconductor technologies.

“Our laboratory even developed the equipment to do that,” she said. “We all had to learn to be glass blowers because we had to be able to repair glass lines and work with explosive compounds inside a glove box then transfer to glass Schlenk lines without exposing them to air, otherwise you could get an explosion.”

To continue this research, Sawrey enrolled in the JDP. In five years, she graduated with both her master’s and doctorate in chemistry. She then continued research as a postdoc at SDSU and, having fallen in love with teaching as a teaching assistant, worked as a lecturer before beginning a career in education and administration at UC San Diego, where she retired with a body of research on STEM education.

Sawrey lauds the way SDSU’s chemistry JDP and STEM impact have grown over the years.

“SDSU can have such an impact around the world,” she said. “I hope those of us on the early end of it paved the way for students who are doing this now.”

Looking Forward

Six decades later, SDSU’s chemistry program continues to grow in ways that have real-world impact on our region and around the world. Faculty research, often conducted in collaboration with current JDP students, continues in such areas as developing environmentally friendly catalysts, studying infectious diseases to improve drug development and creating more targeted cancer medicines with fewer side effects.

This past August, SDSU Imperial Valley celebrated the grand opening of its new Sciences and Engineering Laboratories in Brawley. Timed with the opening of the state-of-the-art space, starting in fall 2026, SDSU Imperial Valley will offer two new undergraduate academic programs in chemistry and electrical engineering.

“Doctoral level research has been key to establishing SDSU's reputation as a leader in STEM,” said Roberts. “Through continued prioritization of STEM programming, the University will support new waves of students and scientific discoveries that will generate far-reaching impacts for decades to come.”