A River On the Rebound

SDSU's plans for a Mission Valley campus river park would connect the riverfront to the community and provide critical habitat for wildlife and native plants.

“The environmental community has weighed in heavily throughout the planning process. The whole park itself has been a product of discussions with a wide variety of stakeholders.”

View the SDSU Mission Valley website to learn more about the site plan and view renderings.

You wouldn’t know it from its bone-dry state during most of the year, but San Diego’s Mission Valley is a floodplain. Flooding is a perennial problem for SDCCU Stadium, previously known as Qualcomm Stadium, which was built in 1967 at the convergence of the San Diego River and Murphy Canyon Creek. Thanks to improper planning and rerouting of existing waterways, when big storms roll through, the San Diego River eagerly jumps its banks and the stadium’s enormous parking lot becomes a blacktop lake surrounding an inundated playing field.

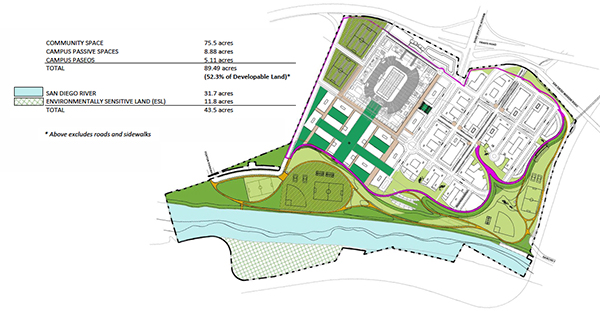

While occasional floods are a natural part of the valley ecosystem, they need not be so destructive or disruptive, said Gordon Carrier of the architecture firm Carrier Johnson + Culture, principal architect for San Diego State University’s Mission Valley campus plan. By incorporating a new, thoughtfully designed and implemented river park at the heart of the proposed campus—nearly 90 acres of which is designated for open space—the university could better manage flooding, provide critical habitat space for wildlife, and connect the Mission Valley community to a beautiful but underutilized resource.

“We’re looking to pull green space from the river’s ecosystem into the site,” Carrier said. “If open space is done right, it can inspire thoughtful development, which sets the tone for the whole site. There are few, if any, opportunities to influence a region like this plan can influence San Diego. Mission Valley is really the epicenter of the entire community, and it’s immensely important to get it right.”

When builders broke ground for the stadium in 1965, they carved out chunks of dirt from the local canyon sides and built, essentially, “the world’s largest pitcher’s mound” for the stadium to sit atop, Carrier explained. They also used concrete channels to divert the natural flow of Murphy Canyon Creek away from the stadium site. Unfortunately, the artificial channel intersects with the San Diego River in an unnatural T-junction, meaning that water careens down the creek and sloshes violently into the river during storms, causing backups and flooding.

READ: The Logic of SDSU Mission Valley

The SDSU Mission Valley river park plan would accommodate Murphy Canyon Creek’s overflow during seasonal flood events by allowing its waters to run into the river with less potential for flooding. Per its design, the flood basin will accept the large surges of storm waters during seasonal storm events.

Inevitably, though, floods will occur when large enough storms hit San Diego. To compensate, builders will raise the site of the proposed campus and its adjoining neighborhood up above the floodplain, using mostly crushed concrete recycled from the old stadium. Tennis courts, baseball diamonds, soccer fields and open green space will sit at a lower elevation, providing recreational space throughout most of the year and an undeveloped buffer for when the rare storm causes the San Diego River to swell.

“It will be green space and athletic fields 98 percent of the time,” Carrier said, “but it will also be a floodplain occasionally. That’s intentional.”

The river park plans also include a number of environmental considerations. SDSU officials, as well as hydrologists, landscape engineers and architects working on the Mission Valley campus plan, have been regularly meeting with environmental interest groups like the Sierra Club to listen to their concerns and suggestions. In response to that feedback, the park will incorporate numerous retention areas known as bioswales that use natural vegetation to filter pollution and trash out of rainwater before it runs off into the river. These bioswales pull double-duty as important habitats for native plants.

While the original plans for the park incorporated a good deal of green space, community members wanted even more, so the architects recently replaced some athletic fields slated for the site’s southwestern corner with additional acres of protected habitat space.

“The environmental community has weighed in heavily throughout the planning process,” said site plan consultant John Kratzer, president and CEO of JMI Realty. “The whole park itself has been a product of discussions with a wide variety of stakeholders.”

Finally, the river park contains nearly six miles of hike and bike trails that encircle the proposed campus, wind through the planned neighborhood and connect the river to other trails throughout the region. The goal, said Martin Flores, director of landscape architecture and urban planning for Carrier Johnson + Culture, is for the river park to provide a connection between the community and the river that has never really existed before.

“We want to open the river up to the community, to retell the story of the river,” he said. “Every time I ride the trolley over the river now, I look down and imagine what it could be. I think it’s going to generate a lot more excitement about the river.”

View the SDSU Mission Valley website to learn more about the site plan and view renderings. CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described how the new plan would manage the flow of water from Murphy Canyon Creek into the San Diego River.