Culture & Identity

Studying abroad is a transformative experience that impacts everyone differently. Your culture(s) and identity(ies) can influence the lens through which you see your experience and interactions abroad, and exploration of personal and cultural identity is an important reason to embark on a global education program. In fact, this is one of SDSU’s university-wide global learning outcomes for students while at SDSU.

Reflecting on what makes you unique and your positionality in the world before, during, and after your program can enrich your experience and maximize its impact over the long term.

Review these culture and identity pages will help you choose a program, prepare for your experience, process it while abroad, and reflect on it when you return.

Identity is complex, and many people hold more than one. Think about what makes you unique and what is important to you. Also think about what types of privileges you may hold when you go abroad.

- What communities, identities, cultures, religion, etc. do you belong to?

- What privileges do you hold when you go abroad (socioeconomic, nationality, education, gender, social groups, etc.)? Awareness and acknowledgement of this privilege will help you to adjust to life abroad and navigate relationships with those you meet.

- What is the history of your identity group(s) in your home country vs. your host country? Will people who look like you, share the same beliefs as you, etc. be in the majority or minority in the country you are staying in?

- What support systems, resources, accommodations, and other needs related to your identity(ies) do you have at home? What is important to you to have abroad? If you are unable to get any of those abroad, what is your plan?

- Are there local laws regarding your identity group, medication, etc.?

- What are you most excited to share about with people from your host country? What are you most excited to learn about people you meet abroad?

Being abroad will challenge your own perceptions about the country you are visiting. It will also allow you to showcase the diversity and nuances of your culture and identity.

When you are abroad, you will be representing San Diego State University, your local community, your location, and your cultural identity. People abroad, and sometimes even your peers, might have stereotypes about those identities and cultures, and you might have stereotypes about theirs.

Challenge yourself to speak with people who do not share your identity, culture, and beliefs while abroad. Uncomfortable conversations are not always a bad thing, and sometimes, the most profound growth can happen from them. We encourage you to lean into that discomfort and engage in critical, meaningful dialogue with others.

Some tips for engaging in critical conversations abroad:- Educate yourself about your own community, politics, culture, and identity before leaving

- Educate yourself about politics, critical issues, identity, and culture of your host country (but stay open-minded when engaging in conversation)

- Speak from your own perspective and avoid speaking for others

- Listen and avoid generalizations and assumptions

- Remember that the individual you are speaking to is only speaking from their own experience and perspective, and things that they say may nt be universally true

- Unpack and reflect upon the conversation afterwards in a journal or with someone you trust

- Disengage if you feel unsafe

While some discomfort is a key part of studying abroad and growth, there is a difference between discomfort and discrimination. If you experience bias and discrimination while on your program, there are resources to support you: https://www.diversityabroad.com/articles/engaging-in-challenging-conversations-abroad

- Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) students

- Black students

- Students with Disabilities

- First generation and EOP students

- Heritage or Native Speakers

- Latinx students

- 2SLGBTQIA+ students

- Native American students

- Traveling with Dependents

- Undocumented students

- Veterans and military affiliated students

- Women

Please consult the following resources as you consider and prepare for your experience abroad.

Learn more about diversity, identity, and culture

The SDSU Global Education Office encourages greater diversity in study abroad, particularly among students of color. Not only will your participation make you competitive for future endeavors, such as graduate school or the workplace, it will also help our programs to better reflect the diversity of our campus and our country.

You may experience anxiety regarding your acceptance in, or ability to adapt socially and academically to, your new culture. As a student of color, you may be concerned about facing potential racial bias and prejudice without the comfort of your usual support system. On the other hand, you may be looking forward to being part of the majority population for the first time in your life. Or, you may be planning a self-discovery sojourn to the country or region of your family's heritage. Whatever reasons you have for studying abroad, you will find that confronting and coping with your adjustment abroad, as painful as it may be at times, can be a positive growth experience. It may not always be fun but, in fact, it can present a unique learning opportunity that will serve you well in the future.

Encountering a new culture will enable you to tap into social and intellectual capabilities you may have never experienced before and force you to discover what you have taken for granted about yourself as an individual and a member of a particular ethnic or racial group. Understanding another culture will enhance your self-awareness, lead to personal growth, and help you develop a greater acceptance of, and compassion for, cultural differences. You may not always admire or endorse the conditions abroad, but it is guaranteed that you will better understand the U.S. upon your return.

Students of Color

While the SDSU Global Education Office recognizes there is no single term with which all students will identify, we have decided to use the term "student of color" in our materials to refer to those students who identify in accordance with SDSU categories of underrepresented populations including African American/Black, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian American, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino(a)/Chicano(a), and Multiracial.

Majority to Minority Status

Students who are accustomed to living as a member of the majority group at home in the U.S. may — for the first time — find they are a member of a minority group while living in their host culture. The reverse may be encountered as well. When anticipated and embraced, these situations can often add a valuable perspective to the study abroad experience.

What is cultural adjustment?

Finding yourself in the midst of an unfamiliar culture can be exciting. Everything around you is new and different: language, climate, clothing, food . . . but other differences are not as noticeable at first.

- How people are expected to interact at home and in public

- How to interpret body language and non-verbal cues

- Even what's considered humorous and what's not . . .

You may sometimes feel confused by cultural patterns with which you are unfamiliar. Adjusting to all of your new environment's cues, both obvious and subtle, can leave you with feelings of uncertainty, frustration, and anxiety.

It helps to remember that you're not alone. Experiencing such stresses is a normal part of the cultural adjustment process, which every study abroad student goes through to some extent. The best strategy is to:

- Educate yourself about the host culture prior to departure to minimize surprises

- Learn about and recognize the symptoms of cultural adjustment

- Practice healthy methods of processing your new experiences

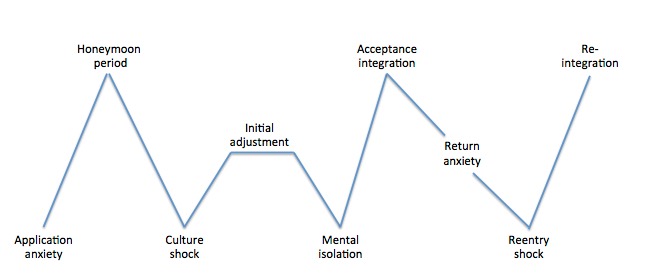

Cross cultural adjustment cycle

Your personal adjustment process will vary according to your background knowledge of the host culture, the length of your program, the level of immersion, and your own experiences.

Each stage in the process is characterized by "symptoms," or outward and inward signs and behaviors. Many people describe the cultural adjustment process as a series of ups and downs:

- Honeymoon period: Initially, you will probably be fascinated and excited by everything new. Usually, visitors are at first overjoyed to be in a new culture.

- Culture shock: You are immersed in new problems: housing, transportation, food, language and new friends. Fatigue may result from continuously trying to comprehend and use the second language. You may wonder, "Why did I come here?”

- Initial adjustment: Everyday activities such as housing and going to school are no longer major problems. Although you may not yet be perfectly fluent in the language spoken, basic ideas and feelings in the second language can be expressed.

- Mental isolation: You have been away from your family and good friends for a long period of time and may feel lonely. Many still feel they cannot express themselves as well as they can in their native language. Frustrations and sometimes a loss of self-confidence result. Some individuals remain at this stage.

- Acceptance and integration: You have established a routine (e.g., work, school, social life). You have accepted the habits, customs, foods and characteristics of the people in the new culture. You feel comfortable with friends, associates, and the language of the country.

- Return anxiety, re-entry shock, and re-integration: Surprisingly, re-entry shock (also known as reverse culture shock) can be more difficult than the initial culture shock of traveling abroad.

Resource material: The International Services Office, The George Washington University, Washington D.C. (Original source unknown.)

You can minimize culture shock by studying your host country's language, culture, and history, and by retaining a sense of humor and a positive outlook. Here are some suggestions to help you overcome the pangs of culture shock when they strike:

- Keep in touch with friends and family at home.

- Try to look for logical reasons why things happen. This may help you view your host culture in a more positive way.

- Try not to concentrate on the negative things about your host culture and do not hang around people who do.

- Make an effort to restore communication by making friends in your host culture.

- Keep your sense of humor!

- Set small goals for yourself as high expectations may be difficult to meet.

- Speak the language of the country you are in and do not worry if you sometimes make a fool of yourself doing it! (Talk to children. Their language level will be similar to yours!)

- Take care of yourself by exercising, getting enough sleep, eating properly and doing things you enjoy.

- Try to fit into the rhythms of life in your host culture. Adjust to their time schedule for meals and work.

- Find out where people meet and socialize. Make an effort to go to those places to observe — and participate.

- Draw on your own personal resources for handling stress. You have done it many times before, and you can do it again!